Transcript

Gissele: Martin Luther King write, does love have the power to turn an enemy into a friend? Does it have the power to heal? This year, we are creating an inspiring documentary, courage to Love the Power of Compassion, which explores the extraordinary stories of those who have chosen to do the unthinkable love and forgive those who are most hurtful Through their journeys, we will uncover the profound impact of forgiveness love, not only on those offering it, but also those receiving it.

In addition, we’ll hear from experts who will explore whether love and compassion are part of our human nature, and how we can bridge divides with those we disagree with. If you’d like to support our film, please donate at [00:01:00] http://www.maitricentre.com/documentary

. Hello and welcome to The Love and Compassion Podcast with Gissele

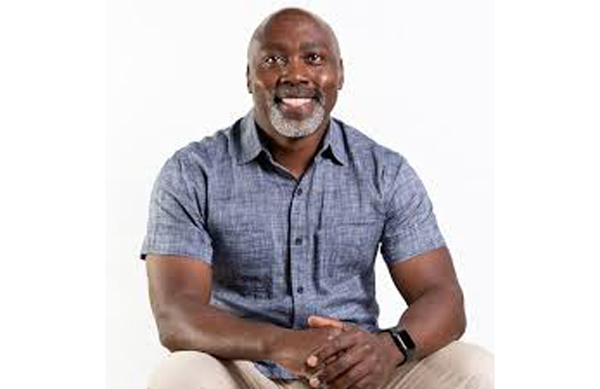

We believe that love and compassion have the power to heal our lives and our world. Don’t forget to like and subscribe for more amazing content. Today we’re gonna be talking about compassion and love in the foster care system. Our guest today is Peter Mutabazi entrepreneur international advocate for children and founder of Now I am known a corporation that supplies resources to encourage and affirm children.

Peter is a single dad, foster parent, who was a former street kid in Uganda. He has worked for Compassion International and the Red Cross. He has appeared on BBC in the Today Show and is author of the book now I am known. Please join me in welcoming Peter. Hi Peter.

Peter: Hey, how are you?

Gissele: I’m good. [00:02:00] How are you?

Peter: I’m good. What a joy to be with you today.

Gissele: Yes. I’ve been, I’ve been following your story for such a long time. I’m such a huge admirer of the work that you do. I followed your story with Anthony and also I used to work in the child protection system and so lots of issues with children that didn’t feel loved and accepted and with sometimes struggling with foster parents who didn’t understand the behavior problems.

And so that’s why your journey is such powerful, powerful reminder of how important it’s to have presence, to have compassion, including for yourself. So I’d like to begin by asking you how you got to this place. Like what was your journey like in terms of going from the streets of Uganda to now having this incredible social media presence and really kind of carving a new way for foster care?

Peter: Well, you know, I was, you know, I was born in Uganda among the poor of the poorest you could imagine. You know I [00:03:00] never had one meal a day. I had one meal every other day. We could not afford beans and potatoes, you know, grew up in a place where I had to go fetch water three to four miles away one way twice a day, like there was no time to be a child.

And two, you know, at age of four, I began to realize that not only are we poor, but my dad was abusive as well. So grew up in a place where, you know, the only words I heard for my dad was, you’ll never amount to anything. You’re nobody. I wish you never born. So I did not have to feed you. And those are the things I heard for my dad.

So for me, internally, life was miserable outside. It was miserable. at the age of, you know, 10, I, I, I knew my father would kill me, so I thought, wait a minute, you know, I would rather die in the hands of a stranger.

So I ran away, and that’s how I became a street kid. And from the age 10 to almost 16. As street kids, we are treated more like stray animals. Like really, people viewed us as we are, we are nobody. We are scum of the earth in some way. Mm-hmm. And somehow we believed it because that’s what we looked like. I mean, I lived in a sewer, I ate from the garbage.[00:04:00]

So all the things people said, you’re like, well, kind of, I’m kind of that way, you know, until I met a stranger who saw the best in me, He saw a kid who wasn’t a thief. He saw a kid who wasn’t smelling. He saw a kid with just potential and he wanted to make a difference. And that’s who changed my life by really offering me two things.

He said, I can feed you once a week or you can go to school where you can eat every day and you, you can survive. And I said, I’ll go to school if there’s food. And that’s how I went to school. And I found out I was smarter than just the food.

Gissele: That’s brilliant. I was wondering if you ever got a chance to ask your benefactor what motivated them to help you?

Peter: Of course I did ask him. I said, you know, but why me? There were more than 3000 kids in the streets of Kampala. So I said, why me? Like, why me? You know, why didn’t you take the other, why me? You know? And he said, you know, I wanted to be faithful, you know, and you always showed up for food. So you are the one I got to really know.

You are the only one. I knew a name, but [00:05:00] you. Always showed up. So it’s like I knew what I cannot do it all I can do for one. And that really, you know, showed a light on, really how we view the world. I think sometimes when we hear a problem, we get overwhelmed. We’re like, that’s too much, you know?

But for him, I think, yes, there were hundreds and hundreds of kids on the streets of Kampala. He say like, I can’t do them all, but I can do one. And that one happened to be me. So that truly is what changed my life.

Gissele: And that’s such a powerful story because you know, like you said, we often think that it’s such a big problem.

Who am I, I am not gonna be able to make a difference. But that person by focusing on one person and then you helping another person, and then it’s just sort of dominoes, right? in terms of creating a, a better, more loving world. And, and how did you transition from that, from school to foster parenting?

Peter: You know, so I went to school in, in Uganda and I went to school in England as well. So that’s how I came to United States, you know, when I arrived in the United States, I, I [00:06:00] struggled seeing how much food was thrown away, you know, and at the same time, knowing that there were kids in the same neighborhood that had no place to go so I could understand.

And I went to church as well, so I couldn’t understand why. They can say, love your neighbor, love the list of these. Yet there are so many kids in foster care. Like I could not understand. we talk the talk, but don’t walk the walk Yeah. And that really, it, challenged me too, but also I feel like I. I live in the most wealthiest place.

I just can’t take for myself like I have to find a way to share with others. But I had traveled all over the world. I had never seen a black person who was adopting in Uganda or in Ethiopia. So because I had never seen anyone who looked like me doing what I love to do. I believed it a lie, like, well, you have to be white, you have to be Caucasian, you have to be married to adopt because they’re the only ones we saw in China anywhere else.

So for me, I didn’t believe that I would be allowed to do so until I. [00:07:00] I walked in and I said, Hey, I just wanna mentor teenagers. Would you allow me to have one or two that I can meet weekly? You know? And the social worker received me, said, Hey, have you ever thought of being a foster dad? I was like, I think about that every day, but I’m not qualified.

And she said, why? I said, I’m single. And literally she said, 30% of our moms are all single. You can be a foster dad. Literally. I said, where do I sign up? I met her on Monday, on Thursday I signed up for classes to be a foster parent.

Gissele: Wow. Yeah, and it’s a lengthy process. I don’t think people realize that. It’s not just like, oh, well I’ve signed up for foster parenting and therefore there, I just get a kid.

Like there’s a whole preparation that needs to happen in order for people to foster. Correct.

Peter: you have to learn one. You know, remember these children belong to the state, so you have to learn the rules and the trauma as well. You know, so it takes between, you know, four months to a year depending where you live, you know, and also the requirements you have to go through in order to be [00:08:00] licensed.

You know, for me it took, took me about five months and then I received my first child, and, and that, that’s where it all began.

Gissele: Yeah. And I, I love that story. I just wanted to go back. Do you feel that you were appropriately prepared for the trauma the kids had experienced? ‘Cause some of the feedback that I’ve heard from foster parents in terms of desiring more information on how to manage because the difficult behavior.

Is really a mask for a lot of the difficult emotions that young people are feeling. Do you feel you were appropriately trained to manage the trauma?

Peter: Yes and no. So for me, remember I was one of those kids, so I went through every trauma most kids have gone through. So I, by experience, I understood that a kid stealing has nothing to do with bad behavior, but there’s a root cause.

There’s a reason why they did. So I stole food because it was the only way I can survive. There was no any other but to say, was I stealing? In people’s eyes, [00:09:00] yes. But on my end, it was survival. I was looking for a way to make it through the next day, you know? So for me, yes, I think the experience really helped me, because I can see from a mile, I’m like, yep, I remember what I did.

I know what sabotage means. But on the other side too, yes, you are right. Especially with the state, when they train you, they train you on the policies of things you do, don’t do things you have to follow. They really don’t equip you on how to deal with trauma, you know? So for me, I had to go an extra mile and enroll in classes for trauma, read books about trauma, and that really helped me.

The other part is I really had to learn more about myself. Like I think as every parent, when you come from a structured parent parenting a child who’s from a non-structured, like those clash. And I think I needed to really revisit my own childhood and say, what will this trigger, you know, what would this cause for me to not be a good parent because I needed to deal with myself first, [00:10:00] and that’s really what helped me the most. I did all the training, not so much for the children, but for my own self. I think like I need, I need to heal, but I need to revisit my childhood as well in order to know how I can be a better parent.

Gissele: Hmm. Yeah. And, The beautiful part about your journey as challenging as it was, it’s given you both perspectives, the perspective of the child who was hurt, the child who experienced trauma, and the survival mechanisms as well as now from the parent who has to help sort of soothe those.

Right. So you had to learn to parent as well, which if you, if you didn’t have that example growing up, must have been challenging.

Peter: Correct? And the man who took me in, they didn’t just put him in school, they brought me to his home. So for the first time I saw a family that sat together, I was like, wait, is that normal?

Like, can people sit together? No fighting and no one hurt? You know? And then I saw how kind he was, the words he used that I never had before. So now I had an example to say, well, if there’s good behavior, now I know what [00:11:00] it looks like, you know? Mm-hmm. And that’s what, what, what helped me as well.

Gissele: Mm-hmm.

Can, you’ve shared this numerous times, but for some of my listeners who may not know your story, can you tell a little bit about how you and Anthony sort of found each other?

Peter: Yes, as foster parents. we do respite, you know, so I had two kids and had them for a year and a half and they had gone back home.

And I can tell you, there’s one thing, they trained me and there’s one thing they did not train me how to say goodbye. You know, so for me, I was not mad, but I was like, I can’t do this like this, this job, this journey is hard. So I told my social worker that, Hey, I need a pause. I need I, I need a pause for six months before I can have a child.

And the kids had left on Monday, so the next, literally on Friday, she calls me, she’s like, look, we need respite. Respite is really when you step in to help a child or a, a parent for a couple days. Usually it’s not a long time, it’s like a week. Mm-hmm. Yeah, so they said they needed a weekend, so I was like, oh, come [00:12:00] on, I can’t do this.

So I said, sure. Once they told me he was left at the hospital, I think that’s what made me feel like, wait, he can’t stay at the hospital Like I got take him. And that was why I said yes, but I agreed to only the weekend. That’s how I met Anthony.

Gissele: Hmm. Yeah. And I found that in my experience in the child welfare system as well, is that because there’s sometimes few foster parents that they will keep like asking and asking and asking for more of foster parents because there aren’t enough homes.

But then that kind of like sometimes can lead to breakdowns of the homes because foster parents will sometimes take on more than they can. Right. And so I think that’s where more foster homes are needed or more resources and support. In terms of you bonding with Anthony one of the things I remember about your story is how like there was a true connection, right?

So from the, the actual [00:13:00] connection to him being adopted did you know quickly that he was gonna be your first adoptive son or was it something that was more like later on in time, you knew that the bond was sort of unbreakable?

Peter: You know, in foster care, as you say, like they don’t tell you.

You get so little information, you know. But with him once they dropped him outta my home, and so I agreed that they will pick him up on Monday. So on Monday, when they get to pick him up, that’s when I ask, so where is he going? You know? So they say, well, all the parental rights have been terminated.

So the only way he can. We can find a place to group home. So I was like, wait, wait, I’ve always wanted to adopt. Can I, you know, I mean literally in one second, I was like, oh, I want him to stay forever literally in front of the social worker who had come to pick him up. I like, oh, no,

Just gimme the paperwork for school. And that’s how I knew instantly. But he’s also, when he arrived at three in the morning that Friday. He said, I said, you can call me Mr. Peter, you know, but he looked in my eyes and said, but [00:14:00] can I call you my dad? You know? So I said, hell no. I was like, hell no.

It’s like, no. And the reason why, because I had had two kids and they had gone back home, who called me dad every day and I’m like, you cannot come into my home and you are only here for a weekend. And somehow, dang that whole dad thing in front of me. Like, I know it. Just don’t, don’t. So that was my reaction first.

Yeah, but for him, he had kind of known since like, you know, I want you to be my dad. But on on the other side, I was like, no, no, that’s not happening. You know, so it on that I said, you know what? This kid knew I’ll be his dad. Yes, I want to be his dad. I.

Gissele: Yeah, and what you mentioned, the grief is real, right?

Like when you have kids that come into your home, become a part of your life, in your kids’ lives, and obviously the point of the system is to reunify as quickly as possible, and that’s, you know, why you’re helping the parents. That’s probably the most compassionate and loving thing you can do.

But allowing [00:15:00] the time or supporting the whole grieving process, I think sometimes. Homes aren’t given enough time to do that by the time a new placement comes in. And so that’s why I love your stories in reminding people that it’s important to take time to grieve that these little lives touch us in so many different ways, and that there’s, it’s a good thing to do, to, feel that, to feel those emotions, right.

Peter: Right. Absolutely. You know, some people tell me, Hey, I cannot force that because I cannot bear letting the child go, you know? Mm-hmm. And most time I just say, you are absolutely right. You know? It is hard. It is tough. But remember, foster care is so they can go back home. So going back home should be the celebration, though the bonding that we had with them was.

Really real and, able to tell people like, Hey, actually you be the best parent for the one who’s scared of that letting go. You are actually the one that need the most because they want that attachment. No one has ever been for them or [00:16:00] there for them. That would really help them grow in that attachment side of the world unless you love them that much.

You know? So it’s been a way of saying like, actually you be the best parents because. Attachment is what they need, you know? Yeah. And I’m always also say yes. It’s really difficult. Like it is hard. It is the hardest part to say goodbye. Yes. You know, you achieved the goal to go back home, but you bonded every day.

You went to bed thinking about this kid every night. It was about them. And all of a sudden gone, yes, It is hard. But you

Gissele: also live in their hearts and minds, and also you can offer a safe place to be if the home breaks down again. One of the things I’ve seen is that there has also been this trend that sometimes kids come in and out of.

Their, their biological homes because parents like, you know, revert or something happens. And so it’s good to have that connection that they don’t have to go into a new home, into a new system. Absolutely. So I think from that perspective is, is really very powerful. [00:17:00] One of the things that I have seen in your stories is talking about how you as a black man adopting white children.

The kind of like reaction very much surprised me, but I thought you handled it. You’ve handled that with such grace and compassion for people. Do you wanna tell a little bit about how you have managed those? what sort of preparation do you have to do when you’re traveling as a black man with your white children?

Peter: So for us is every day, even just, you know, so we have two cars. Every car has a document for every child because that’s how often we get stopped. I’ve been stopped by the police about 11 times because someone reported, but at the same time, I’ve learned how to really not make that personal,

I use that as an opportunity to really share like, Hey, I know, and some are honestly, like Peter, I have never seen a black family with white kids. Like it’s just not something that I’m aware of. So my. Questioning or my reaction wasn’t because I dislike it, I [00:18:00] just, it’s just not there.

And now I’ve taken that more an approach to really educate people, you know, change even when the police comes and say,I know I get this often and I know you have to do your job. You know, so he’s paperwork what else do you need? And most time they’re like, we are, sorry. I’m like, you, you’re doing your job.

You know and to, take it with grace as well, that. People. And, and there are some mean ones like sometimes they, they don’t like to see good in people and they’ll do everything to destroy it. And for me, I have refused to let that get in the way. You know, I love the kids and I want to help And rather approach it with grace, you know change the narrative, you know, for those who want to learn. And for those who don’t want to, I can’t really change them, you know? God will at their own time, but for me to really carry on what, what I get to do, and I’ve also educated my kids, you know, my kids are aware, and I think they’re the ones who take it really hard.

You know, when people are questioning, is that your father? They’re like. Yes, he’s my dad. How dare you? You know? Because for them, they don’t see, they don’t have a black [00:19:00] dad, they just have a dad, you know? Right. Mm-hmm.

Gissele (2): And I think when

Peter: people are questioning that, they’re more like, what? What’s going on?

And they’re the ones who get hurt most of the time. And I’ve kind of really tried to help them, like, Hey, people who look like me, that’s the attitude we get most of the time. Like, it’s just not me. The most majority of people who look like your dad get that reaction or sometimes questioned for no reason.

That I want you to have respect, but also learn how to react as well when you get to see these at school, when you get to see it somewhere else. To really stand up for the people that sometimes are not able to do so.

Gissele: Hmm. Yeah. And I think what you’re doing is fundamentally changing the system through dialogue.

It’s, it could have been very easy for you to get really angry and, and do all of that stuff, and, and then people can feed that anger. But what you’re doing is you are taking the opportunity to educate about the experiences and to get people to understand, okay, this is the process that I have to go through.

Some other people aren’t gonna do that, and these are the things I have to do because I love my [00:20:00] children. Right,

Gissele (2): and

Gissele: so you’re always so child centered. It’s, again, it’s very easy to get pissed off at the people who are making those comments or the cops that are stopping you for the 11th time, but because you’re so child focused, I think to me that that really demonstrate that we can process those things and still be thinking about the impact on our children.

And so I think that is, that is phenomenal, right?

Peter: Yeah.

Gissele: while I was working in the child welfare system I used to have lots of conversations with young people in care about how this system isn’t designed in a way that enables them to have voice and participation in their own experiences.

What have you found as a parent of children who are in the system in terms of some of the barriers to participation and perhaps what we could be doing better?

Peter: Zero. You know, I mean zero. And it begins from how they were taken from their home. Like there’s no warning for them. So they are at school and a social worker shows up with a police like, oh, we are taking you.

And they’re [00:21:00] like, why, why, why? And then they’re moved from home to home. We’ve never been given an explanation of why, you know, I’ve had little ones and I have teenagers. They said they have been in more than 12 homes and no one at, at any particular time did someone say. Hey, by the way, we are moving you tomorrow for reason.

1, 2, 3, 4, none. You know, it’s a decision based on the parents. We, the foster parents and the social workers who decide to say, I want you in my, in my family. Oh, I don’t want you. And they’ll come and pick you up and scramble to take you somewhere. And so it kills the. Their dignity, it kills their voice because from the get go, they just never have an opportunity.

They cannot talk to mom. If they do, they have 15 minutes, to talk to mom. They cannot visit with mom. They have to meet that in the office or in a place where their cameras, so from the get go, that connection with their bio parents is cut off in a harsh way.

That really is hard for them to even think of, Hey, can I voice myself? [00:22:00] Because they’re afraid. I have kids. Every time a social worker comes, they panic. You know, because the only time they have seen a social worker is when that social worker is taking them away, you know? So is the child right to feel so?

Absolutely. You know, and my job is, as a foster parent, is to make sure that, give them a voice, prepare them. You know, I never take a child unless I have an opportunity to visit them, because it’s, if it’s possible, you know, like I would like to meet them where they are. So they feel like, oh, he came to visit us, and then the next week they can say, by the way, the guy who was here came to visit would like to have you.

You know? Mm-hmm. Or sometimes I prefer they come for a weekend and then they go back. So they visit for a weekend and then they go back in. That way, we get to give them an opportunity to say, would you like to stay? You know? Yeah. And 99.9, they always say yes because we give them a little time to really think about it.

But very, very, very few children get that opportunity. So because your [00:23:00] voice is kind of cut off the, you don’t even, you don’t even bother, you know, literally I have a 21-year-old on, on Christmas. I say, what would you like on Christmas? He’s like, well, I. Anything. And I’m like, no, come on, tell me you, you something is like, I don’t know.

And then I go to ask them why they’re like, I asked people ask me for the last eight years I’ve been in foster care, but I never got what I asked for. They always give me handouts or things that don’t fit my age. And so I gave up. That, oh, that breaks me. You know? Yeah. And that’s true. So there’s never voice for them, for sure to, to, you know, court.

We go to court, they never come. You know, they get to, to get, they get the information through the fourth or the third person and sometimes it doesn’t feel like you matter And that really the traumatic situation that really affects our kids in foster care.

Gissele: Yeah. And you know, that’s, that’s sort of the exact feedback I received from young people. It was like it feels like an alien abduction. ’cause you don’t know [00:24:00] where you’re going. You don’t know what time, you know, you usually get stuff moved in garbage bags and there’s just, you go from place to place and.

Like I knew some young people that had been in care 15, 20 years never knew why they were in care. And so then the kids make up stories, right? They internalize this, this must be my fault. And so, and and I, I think there’s an aspect of me that believes that this system is designed this way because that is really how we view and treat children.

How often do we give children the right to have say, the right to, to have, say, over their bodies and say over their minds? And, and so I think we’re learning now, but the, the system is so antiquated it really doesn’t have a lot of opportunities for young people to be able to say, this is my life.

Ultimately I’m a participant. And even if they wanted to return home. Just giving them the reason why they’re not able to go home at this time without needing to shame or, or belittle the [00:25:00] parent. Just, you can speak honestly, because for me, when we’re thinking about love and compassion, you cannot have love without truth,

Peter: right?

Mm-hmm. You

Gissele: cannot love someone if you’re not truthful to them. You couldn’t even have a, a romantic relationship with someone that you’re being untruthful, sore. So how is it that we are not being truthful to young people in enabling them to have participation? I think there’s a lot of fear in the system.

I don’t think workers themselves are always trained, even though some of them are social workers. I see that they’re not trained in emotional regulation.

They don’t know how to emotionally regulate themselves and they don’t know how to hold space for the emotional regulation piece. And so I think that’s where, from my perspective, we could be doing better in terms of training social workers on how to make these systems much more compassionate.

Peter: Right. Yes. Follow the policy, but have the humanity in the middle of it as well, you know? Yeah. And that’s for me where I always feel like it’s, [00:26:00] it’s like a, a mechanical, Hey, here’s how we do. We don’t say this. I’m like, wait, wait. You know? But the humanity doesn’t work in that way. We live in a gray area.

and those policies can’t really function in a way that you ask for. And that’s sometimes the way it feels like your robot, you know, like my social workers, most of them are young and never marry, so they have no clue. You know, I’ll take care of kids sometimes I’m like, okay, how do I go to for advice or how do I go?

To share with this social worker that absolutely no clue on what parenting, and not just parenting, but parenting with trauma, you know? But yeah, I

Gissele: totally, completely agree. ’cause I’ve also spoken to parents in the system, and that was one of their biggest pet peeves.

They’re like, I’m having this. 25, 20 7-year-old with a designer bag coming to my house. I am trying to decide between paying my mortgage or feeding my kids. And then you’re talking to me about how to parent when that person doesn’t have any children. [00:27:00] And at the, at the base of those concerns when I would speak to them was, is this person gonna understand me?

Is this person gonna be able to really help me when they don’t really understand my situation? And so. I think the beauty of your experience as challenging as it was, is that it’s giving you that perspective of kids with trauma and what it’s like to go to all those different environments and not feel like you belong and not feel like you have voice and participation.

Peter: Absolutely. For me, I have a policy that if I have a kid and they’re 13 and above, if they wanna go to court and listen to moms, whatever, like I prefer, so they can hear firsthand, I am not the one passing on information. Like because they’re old enough. Sometimes I feel, I feel like we, we see them as though like.

Like they don’t have the brain. They grew up from this. They understand it more than we do, but sometimes I feel like we are shielding them from what they already know, you know? Yeah. That’s, [00:28:00] that doesn’t make sense. Yeah, that’s,

Gissele: that’s, that’s actually very true. It’s so funny. So I was talking to the children’s advocate office one time.

We were talking about I think it was like healthcare, and she knew that I was working in the child welfare system and she said to me, she goes. Help me understand this. You know, like the trouble welfare system bubble wraps these kids from the time that they come into care and then once they leave care,

It’s like putting a bicycle on the highway and say, see ya. And so there is no preparation, zero for, for independence, because if you have tried to shield them from their life, from their truth, from their experiences, and then when they turn 18. It used to be. Yeah. When it turns 18, I think now Ontario has extended it, but then they’re just like, well see you later.

Now you’re on your own when you’ve paid for everything, when you’ve technically been the parent. I think this is where the struggle is for young people and how there is sort of a, sometimes a linkage [00:29:00] between that. Homelessness or drug use or being trafficked. And so this people in the system and the people that have created the system and the people that perpetuate the system, including myself while I was working in it don’t fully understand the impact of that, of that inability to prepare kids along the way for their future, as you would if you had your own children.

Peter: Well, absolutely, and, and that’s kinda where for me, like I am the child. I’m the parent. I have the kids 99.9 outta the time, but you will not believe the restriction I have for the child. And sometimes I’m like, they are not bubbles, they’re not eggs. You know, these are kids who need to experience, you know, here in the United States, 75% of homelessness.

Are kids from foster care. Yeah. 75% of sex track children are former foster kids. So it’s like literally we are a hose to the, you know, to the outside world,

And, and for me, the, the hardest part is like, [00:30:00] you know, some of our kids have come from a place where they were living by people in a car, literally, you know?

But when they comes to me as foster parents, the regulations and demands, they ask for me out, out of the place. And sometimes I wonder, I’m like, did we just unplug these kids? Put in a place where. It’s, it’s not even a reality for them. They’re like, this temporarily, I don’t really have to work so much because I’ll never attend it.

That we really miss the mark of really helping them navigate what’s the world is gonna be next. You know, that is my frustration that sometimes I can I get accused of leaving in my 16-year-old, old at home. I’m like, he’s 16. He needs to learn.

Gissele (2): Yes. Yeah, to be

Peter: all done.

He has a phone. I know where he is, and it’s a way I can teach them to be independent. And they’re like, but I’m like, co. No, no.

Gissele: Yeah. And this is where there’s the challenge between like foster parents that wanna play that parental role that see [00:31:00] themselves as the parents, but then there’s also this.

Maximum or limit to that. I remember having a conversation with a young person and they said to me ’cause I came for to do a focus group with young people, and they said to me, can you tell me why? It’s okay for me to stay in this foster home and you trust the foster home, but you won’t let me go to a sleepover because you have to criminally check everyone, and so therefore, I’m the only one being excluded.

If you trust my foster parent, then you should trust the decisions they make around my sleepovers. And so I took that feedback back to the organization and kudos to the organization because they changed the policy, but I don’t think they realized what the impact was until you actually spoke to young people.

And so sometimes inadvertently we create these policies for protection, physical protection, not even emotional protection for the physical protection, but it actually ends up causing them. More isolation, less [00:32:00] belonging because we’re trying to, so much to physically protect them that we’re not enabling them to foster those kinds of relationships.

Right.

Peter: Correct. Yes. the stigma we created is us the, the policies and the rules we put around. You know that for me, I don’t really encourage my social workers to visit my kids at school. You, they already don’t like you and you show up at school and tell, and

Gissele: I like that.

It’s true. It is so true. think about it, like stranger danger. we told kids don’t follow a stranger, but here’s somebody who’s showing up at your school just to take you it’s traumatizing. Yeah. They don’t even

Peter: tell you. And sometimes they’ll go for visitation, like, oh, we want to see the child, but at school, and I’m like,you can do that every day.

But remember, it brings more trauma to that child. And shame too, like to come to school. And then they call that kid, Hey, there’s someone you’ve never met. You don’t know at the principal’s office waiting for you. Oh, like, you have no idea what that takes the child to, you know? And, and we even here, we really try to change the way they do [00:33:00] things, you know?

For, for the social worker to trust me, like for 48 hours, if I want my kid to go somewhere, I should not ask for permission. If I can send any of my kids in that place, you should gimme the opportunity to make sure that my child feels at home, but feels they can do whatever they need to do without having to be policed 24 7.

Gissele: Yeah, and I think those, a lot of the policies from working within the system are very based on fear, like something negative happened, and to prevent that negative one thing that happened, we’re gonna wallpaper the system with policies so that it doesn’t happen again. But what they don’t realize is that they’re.

More and more constricting and they are preventing kids from living full lives. Right? Risk is part of life. These kids have survived sometimes horrible things, right? Yeah. So what do we think we’re protecting them from? Like, I mean, I get it. I mean, there’s been abuses and that has been horrible. So we have to acknowledge that.

[00:34:00] And at the same time. Can’t prevent kids from living. What are your thoughts?

Peter: Equip me. Yeah. Equip me to be, equip me for those traumas, for me to really be the best friends I can be, but do not restrict the children. So like in North Carolina here, if you have a, if you have siblings, a boy and a girl, and the boy’s foot is four and the girl is five, they cannot sleep in the same bedroom.

Gissele: Okay.

Peter: Exactly that. they’re saying, well, the, the other one is five. So you’re like, okay, but what, what’s the difference? well, they say, the older kids, they will abuse the little one. I’m like, but it’s not a formula for every child, like that’s.

But it’s not a formula how many Canadians or Americans that have kids that share the room, the majority share the room, you know? Mm-hmm. Especially when there’s same sex. And they are young that day until they get a little older.

We get that. But the restriction they give us sometimes are just so out there. You’re like, [00:35:00] okay, I, I get that. You know? Yeah.

Gissele: And you raise a, a really, really important point, so two things. Number one. It’s, it’s a really great privilege for every kid to have their own room. People don’t realize that, that that’s privilege, right?

Not every household is gonna be able to have one kid per room. And certainly, like when I was a kid growing up, my sister and I shared a room. it’s not that farfetched. The second thing is that. Sometimes the system gets so prescriptive. Like for example, one of their policies was always to have siblings together and keep them right, and that is a great policy if and only if the sibling get along.

I know of young people that were, one sibling tried to kill the other sibling when they were young. Now they get along, but they were placed together and the one kid specifically told their worker, do not place me with my sibling. I don’t wanna be with my sibling. They tried to hurt me. And so in that case, like [00:36:00] these policies become so deaf mute, right?

you’re not listening to the kid’s voice, which is saying, that doesn’t mean this kid didn’t want a relationship with their sibling. They may have a relationship now, but it was at that moment they didn’t wanna be housed, and they should have taken that into consideration. From my perspective, they really gotta look at the bonding.

Sometimes kids are very, very bonded and it’s important to house them together, but sometimes they’re not. And sometimes it’s better for each of them to flourish individually and then come back together later.

Peter: Yes. And, and something we’ve learned too as well, like the common abuser is always a sibling that someone in the, the same background, you know, that’s, that’s what’s common.

Mm-hmm. And that’s kinda what we say sometimes. yes, you want to keep to them together, but we, we think there’s one who’s a culprit that should not be placed in the same home

Gissele: Yeah. They need to heal on their own. Right. They need the, the capacity to be able to heal on their own and have the attention on them perhaps.

Right? Yes. Like, maybe that’s just not the time to keep the, the kids together. I wanted to talk about [00:37:00] being single and, and trying to date as a, a foster parent of many children. What has been your experience?

Peter: Yeah. Well, also the one thing that I’ve learned is. Fostering is a calling. It’s a calling and it’s hard.

You know the, I am able to do it because I love it. I do it in my sleep. I was that kid and I know, I understand my kids and I love doing so, but it’s not for everybody. You know that, that I have to be aware of, like, yes, you might fall in love with someone and love them, but you might make their lives miserable because you’re bringing them in a place where they are not familiar or want to be, you know, and the other part as well, I realized that people, you know people like me because they see me as a dad, but I’m not sure they’re equipped when it comes to handling kids with trauma. Does that make sense? Like they, they idolize you. They see you from a, like a pulpit in some way.

And I’m like, well, but there’s more the ugliness and that that comes with it, that I’m sometimes. [00:38:00] Like they are not prepared for, or they’re not aware, you know? So for me, I think I have chosen to really stick with being a parent along the way. Like one day I’m gonna meet someone who has the same passion and loves kids that who they are rather than who they, want them to make them

is my, kind of goal that I’m content for now. But also too, I think my kids. Because all my kids, their moms were taken away. You know, that I don’t think my kids are prepared to have a mom because they’re afraid that person’s gonna take me away because everyone who came into their lives took their mom away.

You know, that I am not sure that I can meet someone prepared to really help in that route for my kids to know like, Hey, I’m not taking your dad away. You know, I’m just joining. You know, both of you know of, of him and you. So we can be the. Support you. So for me that that’s it, it’s difficult. Also too, I have a little one, I have a 3-year-old and my oldest is, is 18, so I only have between 10:00 AM [00:39:00] and 3:00 PM.

how, how many ladies are gonna meet that are free during that time, you know?

Gissele: Yes, exactly. Exactly. But like you said, I think that the perfect person will come at the perfect time. what you said is very, very fair, which is like, people have to be prepared.

I mean, yeah. There’s like, oh, you, you’re a very loving parent. And you know, people see that, but. Any parent, there’s the traumas, there’s the challenges, there’s the behaviors. And somebody’s gotta be able to understand that it’s not just you, they’re getting right. It’s, it’s your kids. It’s you’re a family unit and they’ve gotta be able to hold space for those difficult feelings and be able to support, not drive a wedge between your kids and what you’re doing.

Right. And I think the, the perfect person will come at the perfect time.

Peter: I hope so. Yes. You know, you know someone that when they hear my child calling me every name, but hey, it’s, it’s their problem, but I’m a daddy and I’m gonna be there for my kid or putting holes in my wall to know like, Hey, it’s just a house.

Come on. You know?

Gissele: And [00:40:00] that’s, that’s so true. you do put boundaries I know recently you had posted about having to say no and how hard it was for one of your children to come back, right?

And so that, that love requires those boundaries. And love requires also sometimes that you pick your battles, right? So the hole in the wall and be fixed, right? You’re really are working on mending hearts.

Peter: Yes, I’ve written a book that is coming out in May and I’m really excited about this book. You know, really sharing my journey of the lessons I’ve learned along the way.

You know, seeing and loving the kids as who they are and, and not taking things they do personally to know that our kids go through a lot of things and my job is not to heal them. My job is to create a space for them to heal at their own time.

Gissele: Oof. Oof. That’s a mic drop right there. And I am sure this book is gonna be so helpful for so many foster parents because I think that’s what happens.

Oh my gosh. you said in May, right? So soon.

Peter: Yeah, it comes out May, yes.

Gissele: Love does not conquer at all. Yes. You know? Yes. Because [00:41:00] I think some foster

parents, some foster parents believe if I just love harder, right? And why aren’t they loving me back?

Why are they doing all of these? It’s like a personal thing. It’s, it’s, it’s not about you. It’s about. The child.

Peter: Right. About the child. Absolutely. You know, I love some of the topics that I write there. You know, you cannot expect a child to grow if you’re not willing to learn. You know?

Gissele: Yeah.

Peter: Parenting will expose your scars as we parent our own scars is gonna come up, you know, so you gotta be prepared to really revisit your own.

Those triggers. Kids

Gissele: know those triggers. they’re just kind of a mirror for you to look at yourself and then sometimes you’re like, oh my gosh, I don’t like the mirror.

Peter: Yes. You’ll not always like your children.

It’s true. Like it’s, yeah, you know, it’s true. You not always like them, but it doesn’t mean you don’t love them. But boy, there are some days where you just wanna just. It’s okay. I love

Gissele: that you said that because I, and, and it’s such a compassionate thing. It’s a self-compassionate thing to admit, which [00:42:00] is.

You love your children. Sometimes they’re not gonna like you and you’re not gonna like them. And how do you navigate those things? And I think sometimes we feel bad as parents. We feel that we’re not good enough. We’re not worthy if we don’t always feel a hundred percent with our kids or give them a hundred percent or do things right.

A hundred percent parenting is a journey and it’s challenging. I think it’s one of the hardest things that you do as a human being. You’re raising another human being. I mean, geez. Right. I don’t think that we give it. Ourselves enough credit, and I think being honest with yourself about what you feel.

I think it’s the sort of like the. Beginning parts of compassion or being compassionate for yourself,

Peter: especially the mom. I think for me, being a male, you know, coming into the world sometimes where we de describe it for only moms, like it is if there, if there’s a man, this is just my, my take.

If there was a man Yeah, yeah. That they came home and somehow that something wasn’t right. I don’t know how I would respond. [00:43:00] the energy that takes me to feed my child or to put him to a naptime or put them in a car is so much stress. Yeah. That I’ve worked in the office.

I’ve never felt so for an entire day working in the office by putting my child in just the car seat I have male friends who complain about they’re not having sex at home, and I’m, now that I’m a dad, like I don’t know how I can do that.

With the stress that you had all day, like, I don’t know. I don’t know how to explain like.

Gissele: No, no, I think I get it. Well, first of all, you’re mom and dad, right? Like you’re both right. So you are doing double duty. So my hat off to single parents because they’re carrying the load and it is such a powerful thing to be there as, as in balancing those roles.

So as a, as a person who has a partner, I’m very grateful to have a partner because you can sort of like say, okay, I can’t do this right now. Like, I’m not liking the children. Please pick up the load. And so single parents. My [00:44:00] hat’s off to you. And at the same time, I think what you are referring to really is, is like the expectations in how much we don’t acknowledge people that are at home and how much work it takes to do the parenting role.

It is exhausting. That doesn’t mean you don’t love your kids, but kids take a lot from you. It takes a lot of effort and energy, especially I want to acknowledge kids with trauma. If they don’t go, Hey, I have trauma. I feel this. Their behavior is their language punched to the wall, poop on the floor.

Behavior problems, truancy crime, that’s how they’re communicating their sadness and fear is, that’s difficult. That’s an additional layer of difficulty that you’re parenting through. So then to have somebody who has expectations of you, I can see where you’re like, yeah. Oh yeah. I mean,

Peter: wait, what you, we are expecting what

My respect for my mom, and my sister is off the hook for [00:45:00] every woman for what they do, the stress and how they’re able to hold it together, still walk out of the home and smile like that is every woman should be given the queen. The queen. Yeah. Totally. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Why they got to do.

And be normal. And, and for me, the hardest part is that even the expectation we put on moms, like to me it is unnecessary. As a male, I find it really disgusting when we blame moms and we never blame the dad. Like, yeah, it took two, but, but yeah.

Gissele: Yeah. Yeah. And, I’ve thought a lot about that.

It’s not just also coming from males, but females too. There’s a judgment between females. There’s that lateral violence, which is like women judging other women instead of uplifting them up, which is very sad. Instead of like judging what, what they should be doing or how they should be doing it. Yeah.

I recently had put a post on TikTok that said The worlds needs more mothers. if we had like, like the essence of mothers, right? Like the [00:46:00] essence of that loving, compassionate, holding space caregiving. We need more of that energy instead of that masculine driven. Power over. I mean, not all males are like that, right?

Like you’re the perfect example of that. But I think we need that more of that motherly energy in the world of like that love, that unconditional love, that acceptance. the nurturance.

Peter: Yeah, the partnership. Like for me, I feel like partnership means. You step in when I’m not doing well, and when you are high, you help me go high.

Like that’s what I think of partnership. You know, having a partner at home that you build each other, you are there for one another. You sense your kids and you are there for them. You know, I have two girls, they’re the best human beings on the planet, you know? Mm-hmm. to see how they adore me as a dad, to know there are some dads who are missing out.

Like there are girls who are missing on that. Yeah. journey of having dad who come and play, who do the hair, who do all that. Like, it’s just not mom’s role. It’s really dad’s role as well, and I enjoy being [00:47:00] so, yeah.

Gissele: I love that. Oh, I love seeing you on social media, like with getting your makeup on it and doing that, and I’m like, that’s so important too.

And it keeps you young to be with children and to. Continue to play and have joy. I think one of the hardest things that we have done to ourselves is stop playing. Is stop being joyful, is stop, like allowing ourselves to flourish. So a couple more questions. The first one is, what is your definition of love?

Peter: Oh wow. Definition of love. You know, love is loving somebody. Even sometimes you don’t feel so loving. Someone is loving someone that not necessarily looks like you has what you have or can offer what you need from them. The loving someone is a sacrifice that sometimes you put yourself on the side for the sake of lifting them up.

That is love. Mm-hmm.

Gissele: Oh, I love that. So last question. Where [00:48:00] can people find you? Where can they buy your books? Not only the one that you showed, but also now. I am known. So where can people find you?

Peter: Well, you can find me on Facebook, on TikTok, on whatever Peter Mutabazi or Foster Dad Flipper but also you can join or check us on our website.

http://www.nowIamknown.org, so where you can buy a book, but the books are available in any bookstore all over the world, so you can get it anywhere, you know this is my new baby and I love it so much because it’s really giving tools to others. Things I’ve learned that I wish I knew, you know, that I would want someone to not fall into what I went through, but.

To be able to say, I can, I can learn one lesson here that would help me be a better parent. Yeah.

Gissele: And I think that’s gonna be extraordinary helpful to foster parents everywhere, and even workers as well, to hear that foster parent perspective on how to be more compassionate and loving within the child welfare system.

Peter: Yes. Mm-hmm.

Gissele: Thank you so much, Peter, for sharing your story. Like. Hug and kisses to all your kids, and [00:49:00] thank you for joining us for another episode of the Love and Compassion Podcast with Gissele Bye bye.